Map of Emilia-Romagna showing the course of northern Appenines

Any major rail link between northern and southern Italy must necessarily pass through the northern section of the Apennine mountain range, which extends across the country from Liguria in the west to Emilia-Romagna and the Adriatic Sea on the east. These mountains also form the backbone of the peninsula, running almost the length of the country from north to south.

In 1864 the completion of a rail line between Porretta, near Bologna, and Pistoia in northern Tuscany was inaugurated by King Vittorio Emmanuele II. A single track road passed through more than forty tunnels and across numerous viaducts. Because of the substantial uphill grades encountered (the maximum being 12%), a

entry at southern portal at Vernio- Cantagallo

spiral switchback loop was constructed to enable trains to make the arduous climb without stalling. The limited capacity of this track was especially acute during World War I, slowing transport of war materials to the north and eventually leading to the planning of a new and bigger line to the east through the mountains.

Map showing route of Direttissima rail line from Bologna to Florence and tunnel section

The new line, known as the Direttissima Bologna-Firenze, included numerous bores though the Appenines from Pianoro all the way to Prato. Construction of the biggest tunnel, known as the Grande Galleria degli Appennini, began in 1923 and took eleven years and 99 lives to complete. It became the engineering showcase of the Fascist regime. From the northern portal at San Benedetto di Val Di Sambro to the southern one at Vernio it covered over 18 kilometers, this time with two

Longitudinal map of Grande Galleria with grades and Precedenze stairwells at center

tracks instead of one, making it at that time the second longest railroad tunnel in the world, one kilometer shorter than the Sempione between Domodossola and Switzerland. The huge project attracted workers from Belgium, Germany and Corsica, in addition to the locals, to comprise a total force of about five thousand. Like many such projects there were fatal accidents, involving gas explosions, roof collapses and flooding. Silicosis claimed many victims as well. Problems caused by smoke from steam locomotives as encountered on the old Porretta route vanished with electrification of the line. As well, the reduction of grades and straightening of the track permitted maximum train speeds to grow from 75 km/hr to up to 180 km/hr. The trip from Porretta to Florence used to take up to five hours; now it took little over one hour from Bologna.

Original entrance to Ca’ di Landino stairwell on hilltop

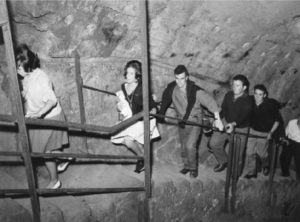

An interesting feature of the Grande Galleria tunnel was the pedestrian access to it from a hilltop. This was excavated at a small village, Ca’ di Landino, about 40 kilometers south of Bologna and 500 meters up. A double stairwell permitted access by tunnel workers and occasional passengers, who had to climb 1800 steps at an inclination of 27° after a primitive lift for miners was disconnected . At the bottom a railroad station within the tunnel itself, called

Passengers climb Ca’ di Landino stairwell

Precedenze, had a double bypass siding, known to railroad workers as the “bananas,” to permit faster trains to pass slower ones. The village of Ca’ di Landino above suffered population attrition when the access stairwell was finally closed some years later. Families of some of the original tunnel workers stayed on permanently in the area but the village itself is now largely abandoned.

Photo of “bananas” switches for priority trains inside tunnel

“Bananas” bypass track scheme at Precedenze

Terrorist Attacks

Symbol of “Ordine Nero”, a pro-fascist radical group from the 1970’s

Symbol of Fascist Group “The Black Order”

Symbol of communist group “Red Brigades”

Radical political groups of Italy’s so-called Anni di Piombo (“Years of Lead” – referring possibly to bullets) beginning in the late 1960’s found the tunnel a tempting venue for creating mass mayhem, especially by using explosives. Groups like the Brigate Rosse and the Ordine Nero hoped to destabilize the government and spark a Marxist-Leninist revolution or the resurgence of fascism, according to some sources.

In August 1974 the train Italicus, heading from Rome to Munich, suffered a huge explosion just moments before exiting the northern portal at San Benedetto di Val Di Sambro. An alleged pro-fascist group had planted a

Burned out coach from “Italicus” bombing 1974

suitcase full of dynamite in a compartment of the fifth coach. In the blast twelve people died and hundreds were injured. Remnants of the timer found suggested the bomb had been set to detonate earlier, in the heart of the tunnel but the train had made better time than expected, thereby saving many lives.

Only ten years later, just before Christmas in 1984, a similar bomb took the lives of sixteen persons and injured over two hundred, this time well within the depths of the tunnel about 8 kilometers after entering at Vernio. This terrorist attack was again attributed to an extreme right-wing movement but some physical evidence suggested it was possibly a reprisal by the Cosa Nostra for mafia prosecutions. Even the notorious boss Totò Riina was implicated but later absolved.

l

Totò Riina going to trial

The bomber(s) had boarded the train Rapido 904 while in the Florence station awaiting departure and left unobtrusive suitcases containing explosives to be detonated by remote control. After the fiery blast the rescue of hundreds of passengers was hindered by the loss of electric power and the need to tow the remaining intact coaches for almost ten kilometers to the northern portal by a diesel engine in dense smoke. Oxygen tanks were supplied aboard to sustain the lucky survivors during the slow trip.

Although it did not happen inside a tunnel this time the bombing of the Bologna railroad station in August 1980 deserves mention for the sheer magnitude of the disaster, which did still occur on the Direttissima line from Bologna to Florence. Eighty six persons died and hundreds injured from a bomb left in the waiting room. Several neo-fascist group members were eventually convicted.

Aftermath of bombing of Bologna RR station 1980

Today the Grande Galleria remains in use for freight and commuter trains, while the new high-velocity trains, TAV, make the Bologna to Florence trip in little over 30 minutes, thanks to the construction of extensive tunnels in a route parallel to the old Direttissima one. The section of TAV to link the piedmont area of Val di Susa to Lyon has been a focus of political contention since the 1990’s, while the strictly Italian sections elsewhere have been completed and are fully functional. Security measures in the new tunnels have been well planned in light of the lessons of the past. Ways to insure safety in the old tunnels are being studied – most necessary in the European country with the biggest network of tunnels, totaling over 1600 kilometers underground.

Memorial to bomb victims showing blast hole in station wall

[Because of the extensive sources already available in Italian I will not provide a version in Italian of this article. Many of the photographs are taken from the Biblioteca della Sala Borsa di Bologna – and an excellent text source is La Direttissima Bologna – Firenze by Maurizio Panconesi, Artestampeedizioni.it; 2017]]

I enjoyed this excellent article, well researched and written….I learned a lot about La Direttissima Bologna – Firenze. Thank you.