Bologna’s monumental cemetery, the Certosa, merits a visit from anyone who wishes to establish a feeling of historical continuity with the generations of Bolognesi that have come and gone. It also provides a tranquil island of peace in the midst of noisy Bologna where one can simply browse over the acres of tombs and savor the rich scent of the many evergreens that grow there. I developed this article with no particular order or agenda but rather to introduce the place to those who might not be aware of it – and there are many who are not, even among the locals. I cannot possibly distill the voluminous history to be discovered here in a brief essay – each time I return for a visit I discover more interesting facts and curiosities which I expect have been overlooked for decades and are ripe to be revealed. It would take months of visits to compile them all.

Many articles on the Certosa have been written in Italian. I did this one in English to involve a larger audience, especially students and visitors who spend time in Bologna. I have borrowed heavily from the texts listed at the end, but all of the photos are from my cell phone – with, alas, a less-than-adequate resolution of detail. I include websites later with excellent photos of professional quality.

Established in Bologna in 1334 on land belonging to the French monks of Chartreuse,* a monastery sprang up and expanded, adding new cloisters steadily around the focal point, the church of San Girolamo.

San Girolamo Church and center of the monastery

The space eventually became large enough to house the troops of Charles V in Bologna on the occasion of his coronation by Pope Clement VII in 1530 as the King of Italy and head of the Holy Roman Empire. This peripatetic ruler of Habsburg lineage at one point dominated Germany, Austria, Spain and Holland as well as the kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia.

Portrait of Charles V by Titian

*The Carthusian Monks even today manufacture the famous French liqueur, which originally was intended to be an elixir of long life but, evidently failing in this purpose, was marketed after 1730 as simply a liqueur.

All was relatively calm until the arrival of Napoleon’s troops from southern France in 1796, having fought with armies of the Piedmont and of Austria. Napoleon, already crowned as King of Italy and Emperor of France, after disposing of the local Cardinal of Bologna, expropriated extensive church lands and properties which he then sold to his friends and others at a considerable advantage.

The Certosa (“charterhouse”) was designated a municipal cemetery in 1801 as a result of Napoleon’s usurpation of religious institutions such as monasteries. The remains of noblemen and prestigious citizens were then interred here after removal from various chapels and family tombs around the city. Gradually space became limited and required the construction of new wings and cloisters.

Many local residents are not aware of the wealth of funerary sculpture hidden behind the long walls surrounding the cemetery, which commands a view of the San Luca Church on a hilltop.

A row of above-ground tombs with San Luca in the distance

There are acres of tombs, in a labyrinth of corridors, some underground; there are porticos as well. The stone or bronze figures and castings over the graves seem to appeal to passersby for a moment of meditation and for the recognition of those who lie within. I found it astounding that so many precious works of sculpture are gathered in open galleries and chapels, totally at the mercy of anyone intent upon vandalism. Although a few surveillance cameras can be seen at the entrances I never saw anyone on the grounds except for an occasional maintenance person or a relative visiting a loved one’s tomb.

One of many enclosed tunnels of tombs

The cemetery remains fully functional today and has several large cypress-bordered fields for new burials. Above-ground tombs bearing inscribed plaques and often photographs of the occupants are arranged in parallel rows several hundred feet long and two stories in height with mobile ladders available for those who wish to visit the “higher-ups” not reachable by the staircases. It’s easy to lose your way navigating through the maze. There is even a serene “Garden of Remembrance” nearby for relatives to disperse ashes of loved ones from the on-site crematorium.

Zanotti mausoleum

Funerals at the Certosa have taken place daily from the beginning of the Nineteenth Century. Tomb styles reflect the fashion of the times, ranging from classical revival through the “Liberty” style, popular at the turn of the century. The more recent tombs feature simple marble slabs and headstones. The more prosperous families over the years have erected mausoleums of widely-differing styles to house all their departed members and glorify their social standing

Sarti mausoleum

At the main entrance of the Certosa is a pair of Piangoloni, that is, “Weepers,” high above on the gates, sculpted in terracotta by Giovanni Putti in 1809, to greet mourners a s they arrive and to set the proper tone for their visit.

s they arrive and to set the proper tone for their visit.

Putti’s Piagnoni

The faces are obscured by the cloaks with their flowing folds. The theme of the hooded figure crouching near the departed is often repeated in the older sections of the cemetery.

It seems ironic that Giovanni Putti, who worked so hard to create majestic sculptures for the Certosa, should end up in a humble, inconspicuous tomb on an unlit corridor of the very cemetery that he helped to elevate to international standing. The inscription merely reads “Giovanni Putti, Sculptor – 1847.” Apparently the family had other plans for the sum that a bigger tomb would have cost.

In an alcove across from the entrance to the San Girolamo church, which was the headquarters of the old monastery, one finds the tomb of Alfonso Ropa, a tobacconist who was killed in his shop in 1945 by the Allied forces during a bombing raid.

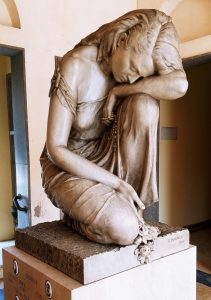

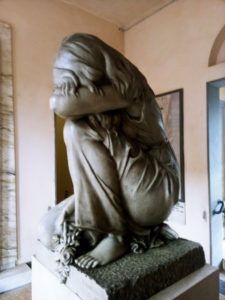

A statue of a grieving girl, sculpted by the local artist Renaud Martelli in 1947, conveys considerable emotional impact.

The neoclassical facial features combine harmoniously with the more modern lithe and graceful attitude of the female figure. She gives the impression that she could get up and walk away if asked.

Martelli cherubs

Martelli was a prolific artist, responsible for over one hundred works in the cemetery, ranging from marble statues to bronze tomb embellishments. He seemed to enjoy creating small, playful angelic figures, possibly to alleviate the sadness of the grave sites. In some churches elsewhere in Bologna he created bronze relief murals of unlikely and fanciful content, one of which, for example, depicts San Giuseppe and a small child, with Albert Schweitzer and Martin Luther King standing beside them.

Some affluent families commemorated certain members with lengthy inscriptions affixed to their tombs. This tablet to Gian Luigi Protche tells of his birth in Metz, education in Paris and prodigious engineering feats especially in building bridges, culminating in creating the first rail link through the Appennines between Bologna and Pistoia. The plaque describes in flowery prose how he was awarded Italian citizenship for his merits and that he died “Christianly” in 1886.

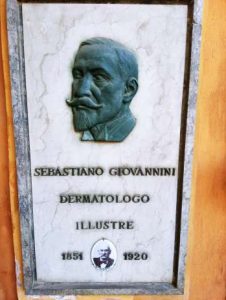

A local dermatologist in bronze relief

Titles of Cavaliers of the Republic, Barons, Dukes, and the like were usually included in the epitaphs of important persons. This physician was merely described as “renowned”. His photograph is seen below his bronze relief cameo.

A hooded piangente and a weeping guardian angel

The large monument (1815) to the Ottani family was the fruit of Giovanni Putti’s sculpting and Angelo Venturoli’s design. It features a hooded figure clasping an urn next to which a genio funebre, the counterpart of a guardian angel, stands weeping and holding an inverted torch, representing the extinction of life. A large seated figure with cloak, cross and raised arm stands above. The complete allegorical work symbolizes Religion, Love and Conjugal Fidelity.

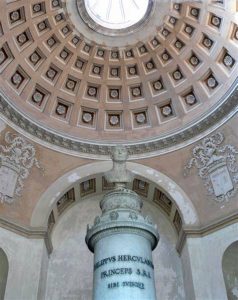

Angelo Venturoli designed the ceiling of the chapel, inspired by that of the Pantheon, in the Cella Hercolani, which contains the bust of Bologna-born Prince Filippo IV, a Bolognese politician and descendant of the man-of-parts Principe Filippo Hercolani I who was also a politician but a noted bibliophile and scoundrel to boot  . Filippo I was implicated in unsavory behaviors including a murder-for-hire plot. Even his new wife from Lucca speedily entered into a convent after their wedding in order to escape him. This memorial shown here was created in homage to his less colorful but more digestible relative, Filippo IV, who was a senator, patron of the arts and an acquaintance of Napoleon.

. Filippo I was implicated in unsavory behaviors including a murder-for-hire plot. Even his new wife from Lucca speedily entered into a convent after their wedding in order to escape him. This memorial shown here was created in homage to his less colorful but more digestible relative, Filippo IV, who was a senator, patron of the arts and an acquaintance of Napoleon.

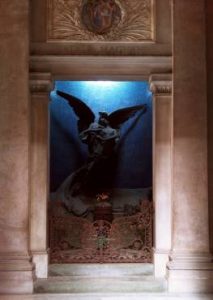

Pasquale Rizzoli created the magnificent bronze Liberty-style monument below, which is set in a niche lined with blue mosaic and illuminated by a skylight in the Cella Magnani. It reflected the trend away from classical revival toward the Liberty style, popular at the time of its creation in 1906. Rizzoli succeeds in portraying a sense of an ethereal, upward flow of the figures, which represent an angel whose face shows loving tenderness while he accompanies the soul of a lifeless woman toward heaven. The base of the sculpture, not seen here, is richly entwined with the flowers so characteristic of the Liberty style, which originated in the orient thanks to art objects imported by Arthur Liberty to his store in London in the 1880’s

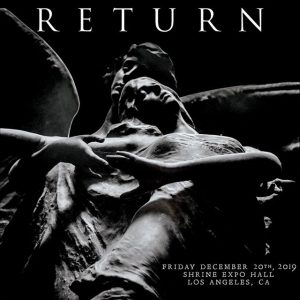

A rock music group, My Chemical Romance, from Newark, New Jersey adopted this sculpture for its reunion tour poster in 2019, as well as forming a holographic back drop on a huge screen during their performance. I would be interested to know how a sculpture from a cemetery came to be publicized in this way!

Concert Poster

The crescent mosaic adorning the Monari-Robbi tomb below again illustrates the floral embellishments typical of the late 19th century style in Italy. The fruit and plant entwinings suggest the possible influence of Luca Della Robbia, born centuries earlier in Florence, who perfected this plaster sculpture technique.

Below is a large composition that marks the Bisteghi tomb, completed in 1891 by Enrico Barbieri. The overriding presence of a rather impassive angel dominates the scene of the dying man attended by his wife, devoutly kneeling, stiffly, at the bedside. A walk around the monument reveals several interesting perspectives, including that of the comfortable-appearing disposition of the bed cushions, a detail reportedly suggested by Barbieri’s friend Luigi Serra, who is famous for portraiture and watercolors in Bologna.

Barbieri had the reputation of being a very slow worker, drawing up and redrawing plans multiple times before applying his chisel. He spent ten years in creating this monument, which had been commissioned by Bisteghi’s family with the proviso that a munificent sum of at least 12,000 Lire be spent on it. It was.

The Certosa is rich in large monuments, both outdoors exposed to the weather and indoors. It is rather amazing that the precious works have not fallen prey to hands of vandals, which are so active in Bologna with spray paint and hammers elsewhere. As an aside, for anyone who has visited the Museo Capitolino in Rome the absence of noses on almost all of the hundreds of busts is striking – either the work of Father Time or of vandals. So far this has not occurred at the Certosa, in part because the sculptures here do not go back earlier than the 17th Century.

I find the Montanari sarcophagus by Diego Sarti and Attilio Muggia in 1891 interesting in the way that the grieving female is resting, head sustained by her left arm, on a bunch of flowers and, rather than looking sorrowful, looks instead rather bored or, at best, contemplative. The copious folds of her gown are impressive. A child figure of Mercury sits above the tomb.

The Montanari tomb

One monument that I find much more curious than attractive is that created for the famous motorcyclist Olindo Raggi, who was killed in a race on the Montlery autodrome near Paris in 1926 while he was trying to break the world speed record. His attempt was lauded by the Fascist elements of society at the time which wished to show their ethnic superiority. The monument shows Olindo’s corpse being cradled in a pietà fashion while a group of motorcyclists stand on the left – with a cycle included – and a group of grieving young women on the right. This tomb is conspicuously placed at one of the main entrances to the cemetery.

Olindo Raggi’s tomb by Armando Minguzzi

Patriotism is a theme also in the monument by sculptor Vincenzo Vela, who was angered by the Austrian occupation of the Lombardy and Venice regions of Italy. In 1848 he participated in an armed uprising against the occupiers which lasted for five days – Le Cinque Giornate Di Milano – and culminated in their expulsion. The woman, carved from marble, is seated in the center of an impressive niche. Her expression is thought to reflect the preoccupation and unhappiness of the oppressed Milanesi before their liberation, which was considered the first war of Italian independence.

which lasted for five days – Le Cinque Giornate Di Milano – and culminated in their expulsion. The woman, carved from marble, is seated in the center of an impressive niche. Her expression is thought to reflect the preoccupation and unhappiness of the oppressed Milanesi before their liberation, which was considered the first war of Italian independence.

A bronze relief inscription in Latin above the monument reads, Vita Brevis – Gaudia Rara – “Life is short and happiness little.” Evidently Vela was profoundly depressed!

General Joseph Radetzsky, for whom the famous military march is named, was one of the Austrian occupiers who was sent packing. This march often announces the opening procession of the grand New Year’s Ball in Vienna.

Bottoni monument commissioned by Mayor Dozza

In stark contrast is the contemporary monument to the fallen Italian partisans during the Nazi occupation of Italy. Built in 1959 this curious structure, which to me resembles a nuclear power plant, contains statues on the inner walls posed to appear climbing upward toward heaven; on top one can see a standing figure. When one enters below the darkness the other statues are silhouetted against the brilliant daylight entering from above. Giuseppe Dozza, a much-esteemed mayor of Bologna for many years, was himself a partisan during the war and wished to commemorate his comrades by commissioning this monument.

darkness the other statues are silhouetted against the brilliant daylight entering from above. Giuseppe Dozza, a much-esteemed mayor of Bologna for many years, was himself a partisan during the war and wished to commemorate his comrades by commissioning this monument.

Two marble soldiers stand guard over more traditional tomb for over 3000 soldiers who died during WWI along with some others who died early in WWII. This vast tomb has an underground entrance and is roofed by numerous slabs of travertine marble.

The sarcophagus of Ennio Gnudi is interesting for two reasons: first, it appears to be sinking into the ground (or rising from it, depending on one’s perspective). Gnudi, who died in 1949,was a politician and railroad union official. Second, the pall bearer at the head of the casket on the left is a female figure, perhaps paying homage to the growing women’s work force which appeared during WWII.

official. Second, the pall bearer at the head of the casket on the left is a female figure, perhaps paying homage to the growing women’s work force which appeared during WWII.

The father-and-son tomb of the Frassetto family, designed and realized by Farpi Vignoli in 1950, depicts the father, who was an anthropologist at the Bologna Athenaeum, and his son, who was killed in WWII. One can distinguish the father by the skull cradled at his elbow, while the son, on the right, wears military garb and holds a swagger stick. The two seem to be having a lively chat.

Other tombs feature children, for example this carving of a girl, with eyes closed, seated in a padded chair and covered with a lap robe. A photograph of the unfortunate young lady is mounted on the base.

The figure of the young girl kneeling at the Minelli tomb probably depicts a grieving grandchild lovingly tracing the stone with her fingers.

The affectionate representation of a mother holding her child apparently while visiting the grave of a loved one shows remarkable detail and realism.

loved one shows remarkable detail and realism.

In the adjoining photo a young mother nurses one child and restrains the other one by holding his arm. Note how the tip of the mother’s sandal protrudes just beyond the edge of the base, thus lending a contemporary touch to an otherwise neoclassical composition.

Representations of small children in the Certosa cemetery statuary lighten its lugubrious atmosphere and suggest the perpetuation of life through the generations. Cherubs and other playful winged celestial creatures adorn numerous graves. The sculpture of a little girl standing on tiptoes to place a bunch of flowers at the base of a bust of her grandfather is a touching example.

Beau Memorial Bas Relief

The motif of the grieving relative bringing flowers to the grave is a very common one. The young woman resting her head on her hand as she places flowers on the tomb is yet another example, similar to the woman sculpted by Martelli at the Ropa tomb, shown earlier.

Some of the tombs have an eerie, frightening aspect, quite unlike the ones shown above. The black-hooded figures prostrate on the Sassoli tomb with black crepe between them provide a stark contrast to the brilliant white marble sarcophagus.

The black-hooded figures prostrate on the Sassoli tomb with black crepe between them provide a stark contrast to the brilliant white marble sarcophagus.

The Grim Reaper of the Fornasini tomb holds his cloak to hide his grisly countenance as he lurks in a dark niche. Below is written Mutae Mortis Magna Vox, or “The Loud Voice of Silent Death.” Attempts to clarify the sculptor and why this curious phrase appears on the tomb so far have failed. Don Giovanni Fornasini, who was recently elevated to sainthood by the Holy See after his martyrdom as a resistance fighter against the Nazi troops at Marzabotto in 1944, seemed a likely candidate to have been entombed here – but evidence to the contrary exists.

This very stylized contemporary bronze figure reclines over the graves of nuns from a local order. It is in bizarre contrast to the many classical sculptures that surround it.

Veiled figures appear as well as hooded ones.

De Maria’s “Velata”

The Caprara tomb houses the remains of Carlo Caprara, (1775 – 1816), a minister of the Kingdom of Italy and once host to Napoleon Bonaparte in his home in Bologna. The Velata, as known to Bolognese visitors, is part of a larger montage by the sculptor Giacomo De Maria and was completed about a year after Caprara’s death. Marble at that time was scarce and very costly to import. This sculpture was imitated by De Maria’s contemporary Giovanni Putti elsewhere in the cemetery, and apparently the two artists respected each other’s works and exchanged ideas.

The veiled statue by Giovanni Putti on the right is part of the tomb of Triofi Pepoli, created in 1823 to commemorate the death of Guido Pepoli’s wife, Geltrude, at age 30. The woman sculpted here wears a gauze-like veil which begs to be touched to realize that it is actually marble. One foot rests upon a skull, which likely represents victory over death. Putti worked for some years in Milan and contributed to the completion of the façade of the Duomo, after which he returned to Bologna where he specialized in funerary sculptures. His technique is described as linking neoclassicism with realism, a growing trend in the 19th century.

The veiled statue by Giovanni Putti on the right is part of the tomb of Triofi Pepoli, created in 1823 to commemorate the death of Guido Pepoli’s wife, Geltrude, at age 30. The woman sculpted here wears a gauze-like veil which begs to be touched to realize that it is actually marble. One foot rests upon a skull, which likely represents victory over death. Putti worked for some years in Milan and contributed to the completion of the façade of the Duomo, after which he returned to Bologna where he specialized in funerary sculptures. His technique is described as linking neoclassicism with realism, a growing trend in the 19th century.

“La Notte”

Ercole Drei realized this allegorical figure, “The Night,” in 1955 at the Barbieri tomb. The right leg is rather well defined and the figure shields herself from the daylight with a cloak. Drei was commissioned to produce an equestrian statue of Gen. Pulasky in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1953. He later became director of the Accademia Delle Belle Arti of Bologna for many years.

The Trentini monument, executed in bronze in 1924 by Pasquale Rizzoli, is very complicated visually as well as structurally. There is a bronze bust on top, out of the picture. In the center an angel bends to pluck a flower, representing the soul of the departed, from the arbor vitae which has been snapped in half. It is said that this large work revived interest in creating grand-scale monuments. This one shows the Liberty influence, in vogue at that time. Rizzoli’s Cella Magnani sculpture shown earlier has many details in common with the Trentini work, as one might expect.

Angel by Orsoni

Another bronze angel sculpture adorns the Nannetti family tomb and was completed in 1916. Arturo Orsoni, one of thirteen sons of a blacksmith from Budrio, a farming town near Bologna, sculpted numerous single figures, particularly religious ones, which can be found around the city.

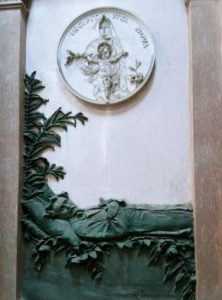

“He begins a new life” is

written on the plaster portion

At first glance this bronze bas relief looks like a view from a window because of the branches with leaves. I was unable to identify the sculptor.

The saddest sections of the cemetery are those reserved for children. The authorities have apparently relaxed the otherwise stringent rules of gravesite uniformity to permit grieving parents and relatives to express their love of their departed little ones in their own way. One knows immediately when he reaches the children’s graves because of the colorful playhouse-like structures, numerous small plantings and an abundance of toys strewn over the graves. While the plastic items are durable the traditional teddy bears and dolls left there evoke even greater pathos as they deteriorate in the passage of the seasons.

Vanessa’s Tomb

Chiara’s tomb

Basketball was this youngster’s passion when he died

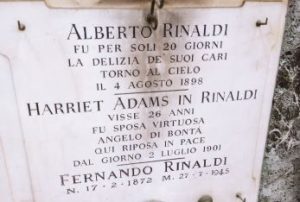

Rinaldi family tomb

The epitaph on the tomb of an Italo-Anglican family reads “Alberto was the delight of his parents for only twenty days before returning to heaven; he died on August 4, 1898. Harriet Adams (his mother) lived for twenty six years, a virtuous wife and an angel of goodness, and rests here in peace.” Fernando, her husband, managed to live until age 73 (the wife’s maiden name is always conserved in Italy with in Rinaldi appended to indicate her marital status)

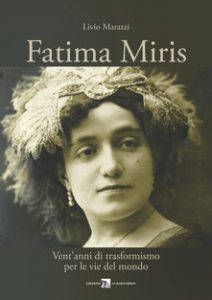

On a lighter note the story of the occupant of the next grave is truly unique. Born Maria di Arco Frassinese, from early childhood she learned to perform in variety shows assuming the stage name of “Fatima Miris,” eventually performing around the world. Not only was she able to sing in all musical ranges but also played numerous instruments skillfully. She could delight audiences singlehandedly for up to three hours with her many talents, especially as a “transformist,” changing from female to male characters instantly and using ventriloquism to enhance her performance. In addition she was an accomplished marksman with firearms and in throwing knives — as well as being a magician and illusionist!

instantly and using ventriloquism to enhance her performance. In addition she was an accomplished marksman with firearms and in throwing knives — as well as being a magician and illusionist!

Fatima Miris

Doubts about her gender were clarified after she gave birth to a daughter, Giovanna (“Joan of Arc”), although resemblances to the Parisian Victoria Grant who inspired the film Victor Victoria are clear. When Fatima died in 1954 she stipulated that her funeral be marked by a musical band and that her daughter appear at the ceremony in a red dress.

Biography by Livio Marazzi

Over the years the original grandeur of the old Certosa has gradually given way to the exigencies of limited space and limited funds. In order to create new grave sites the cemetery must exhume the remains of those buried for over ten years; their bones are then placed in a common ossuary. Modern, simple gravestones have replaced the meticulously sculpted monuments of the last century. The rich and famous, however, continue to be commemorated ostentatiously. As they did centuries ago by erecting competing towers in the city, today’s wealthy families build towering mausoleums in the midst of the lesser graves to flaunt their perceived social superiority. Unfortunately architectural artistry is often lacking, and the finished product looks more like a huge comfort station or telephone booth than a family’s home for eternity.

A glimpse of a few representative modern tombs provides a sense of how things have changed. Some still strive for originality . . .

a marble stone with photograph and votive electric candle

a simple rock headstone gives free rein to imagination

a photo applied to a surfboard?

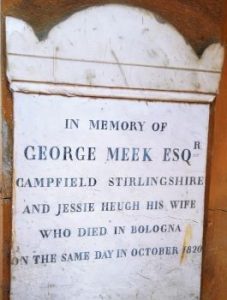

The Certosa has two separate sections for non-Catholics: the Hebrew Cemetery and the Anglican Cemetery. Both are much smaller but offer insights into some of the early immigrants to Bologna. One wonders at what tragedy befell this English couple to cost them both their lives on the same day in 1820.*

The Certosa has two separate sections for non-Catholics: the Hebrew Cemetery and the Anglican Cemetery. Both are much smaller but offer insights into some of the early immigrants to Bologna. One wonders at what tragedy befell this English couple to cost them both their lives on the same day in 1820.*

- The Chief Librarian at the Bologna branch of the Johns Hopkins University, upon seeing my bewilderment, delved into this mystery and quickly discovered that the couple , as well as an infant child not mentioned on the epitaph, all died of malarial fever. Because the wife died thirty minutes before the husband the wife’s family became the beneficiary of her estate.

In conclusion I list my sources of information, such as they can be when they refer to persons who lived a century or two ago and often had only shreds of biographical material available. I invite those who read Italian or those who wish to view more spectacular photos to consult the sites:

- Certosa di Bologna: Arte, Storia, Memoria by Roberto Martorelli, 2016; Edizioni Minerva, www.edizioniminerva.com

- Storia e Memoria di Bologna: www.storiaememoriadibologna.it/certosa

- Fatima Miris by Livio Marazzi, Edizioni Al Barnardon, 2017; www.albarnardon.it/fatima-miris

- Photographs: www.guidobarbi.it/certosa-di-bologna

- Photographs: sevbru.altervista.org/prof

A playful Martelli tomb decoration

The words of Marcus Tullius Cicero seem most appropriate for closing:

The life of the dead is placed in the memory of the living

Fantastic effort!

Wonderful. Thanks for sharing such a remarkable wealth of history right here on our doorstep.

A fascinating account and an invitation to visit the Certosa sooner rather than later! Thank you!

A very scholarly but very readable little history on a little place of history. Thank you.

Paradoxically lovely.

This is wonderful. Can’t wait to get to Bologna and take your tour

What an informative and enticing work. A visit to Certosa is on my list for next visit to Bologna. I’ve always gotten a kick out of the photographs often seen on Italian tombstones, but this statuary certainly takes it to a higher lever. Also, it was interesting to learn that Green Chartreuse was an elixir for longer life. In an ironic twist, my husband used to buy shots for people who were irritating him!

La tomba Fornasini è la tomba nella quale è sepolta la Famiglia Fornasini che nulla a che fare con Don Fornasini. La tomba rifatta negli anni 30 da Francesco Carlo Fornasini contiene sette persone. Vive oggi la fondazione Dott Carlo Fornasini in poggio Renatico sua creatura. La frase vuole dire che il silenzio della morte non può nulla contro la imperitura fama (data dalla Fondazione appunto)