San Ruffillo station as it appears today

My fascination with the subject of railroads drove me to tell the story of the Grande Galleria degli Appennini in Part 1 of this pair of articles. As an offshoot it also led me to want to learn more about the Italian Resistance fighters during World War II – the partigiani – after I visited the railroad station of San Ruffillo, on the southern edge of the city of Bologna. Although the station today serves only a few commuter trains and is operated remotely with no station personnel at all, it stands silently like a tombstone to mark the spot where, toward the end of the war, over a hundred captured partisans were executed by Nazi firing squads and buried summarily in craters from allied bombs dropped around the station’s perimeter.

Ruins of San Ruffillo and surrounding damage from bombings

Gen Erwin Rommel

Following the armistice in September 1943 the German Army Group B under the command of General Erwin Rommel, better known for his Afrika Corps successes, maintained its grip on the province of Emilia Romagna and its regional capital Bologna, in an attempt to forestall any Allied advance from southern Italy. The Germans quickly disarmed most Italian troops and rounded up over 400,000 soldiers who were then sent to internment camps in Austria and Germany. Confusion reigned as the Italian soldiers left behind switched alliances and did not receive orders from their superiors on how to proceed; many detachments simply disbanded. The Appenine hills around Bologna became fertile territory for the spawning of resistance fighters, who deeply resented the occupiers. Various groups in the city clandestinely organized as well into partisan “brigades,” which carried out numerous acts of sabotage against the German forces. The partisans in the hills met secretly in farmhouses and were supported by the local peasants who fed and housed some in their outbuildings. Some families even contributed all their savings and livestock to the cause of ridding themselves of Nazi oppression.

Armed partisans seen under the Two Towers

Brigades of partisans tended to gather under their own political ideals. The Brigata Gianni Garibaldi, for example, was composed largely of Communists, while the Matteotti and Mazzini brigades included Socialists, Christian Democrats and other factions. Catholics comprised the bulk of the Stella Rossa, which was quite active in the area of Monte Sole around Monzuno, Grizzana and Marzabotto, where the bloodiest massacres of partisans and civilians occurred. Many brigades had several numbered subdivisions based on geographical provenance; the 7th division of the Briigata Garibaldi was most active in this area.

Certain charismatic figures emerged from the brigades. Irma Bandiera, age 29, a member of the 7th Garibaldi brigade and an avowed Communist, was active in the sabotage of Nazi vehicles and armaments, inflicting important losses and hampering the German supply chain. She also smuggled weapons and documents for her fellow partisans.

Irma Bandiera

Nicknamed “Mimma,” she was caught by German soldiers as she returned home to Bologna from a mission in late 1944. Under the direction of Capt. Renato Tartarotti, commander of the local GNR, that is, Italians still loyal to the Fascist regime, she suffered six days of torture and was finally shot to death in front of her parents’ home near San Luca, where her body was left on view in the street for a day. It is said that she never gave up any information during her capture. Tartarotti was later arrested and executed for his actions.

Tartarotti pictured moments before his execution for war crimes

Irma, who received a gold medal for valor posthumously, was one of many thousands of women who sustained the anti-Nazi cause across Italy, not only in combat but in auxiliary roles such as nurses, couriers and supply gatherers.

Female partisans played important combat and support roles

“Il Lupo” Mario Musolesi

The leader of Stella Rossa, the brigade intimately linked to the people of the Monte Sole area, was Mario Musolesi, known as “Il Lupo” (the wolf). He was thought to be essentially apolitical, driven mainly by his hatred of the Nazi occupiers. As a child he was noted to be exceptionally courageous. His sisters and brother participated in clandestine brigade activities under his guidance. Mario had learned the techniques of guerrilla warfare and had escaped capture by English forces in Libya, returning to Italy in 1943 after being injured in combat. He founded the Stella Rossa upon returning home to Monte Sole. After hitting a fascist who accused him of distributing antifascist flyers some family members were arrested and his house burned. He even survived a stabbing attempt while sleeping thanks to an alert comrade. His group so succeeded in inflaming the German command through train derailments and attacks on road convoys that the Germans inflicted severe reprisals on the entire local population with the excuse of weeding out the partisans.

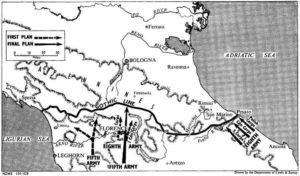

Map of the Gothic Line

Many massacres of civilians took place along the northern Appenines. Hitler wanted an empty buffer zone along the Linea Gotica, a virtual fence running through the hills, to hinder Allied advances. In August 1944 at St. Anna Di Stazzema in Tuscany almost 500 civilians were killed to clear the space of possible sympathizers with the Allies. While the men escaped to the hills to avoid capture and deportation the SS troops eliminated mostly women and children left behind in their homes, which had been at first thought safe.

Map of area of main activity of the Stella Rossa Brigade, with Marzabotto at center

The bloodiest massacre took place at Marzabotto in early October 1944, in which over 1000 people, mainly women, children and the elderly were killed by SS troops of the 16th Panzer division under orders of Maj. Walter Reder. “Lupo” Musolesi was killed along with ten members of his brigade when surrounded in a farmhouse there on September 29, 1944, and his fiancé, also a resistance fighter, was killed the same day in a skirmish not far away.

Reder was later arrested, tried in 1951 for war crimes and sentenced to life imprisonment. He claimed he had gotten orders from above to destroy the enemy indiscriminately and at any cost. Reder was pardoned by Premier Craxi in 1985 and sent to Austria, where he quickly recanted the apology that he had extended to the survivors of Marzabotto in order to facilitate his release.

Gen Walter Reder under arrest

As the Allied forces advanced northward and threatened to penetrate the Linea Gotica, partisans in Bologna carried out other operations to weaken the German occupiers. The famous Baglioni Hotel in the city center was the target of the Brigata Garibaldi. It had been commandeered by the SS officers as their headquarters. The partisans attacked on two occasions in late September 1944, overcoming the guards and placing 90 kg. of dynamite on the first floor, even while the German officials and even sympathizer Capt. Tartarotti were partying with prostitutes in the ballroom. The first bomb failed to detonate but three days later two bombs at the front entrance did the job and tore out the façade of the building.

Interrogation from “Rome: Open City” 1945 by Rossellini

To intimidate the locals even further the Gestapo ran several interrogation and torture chambers around the citycenter, operated in concert with Compagnia Autonoma Speciale or “CAS” staffed by Italian Nazi sympathizers,including the infamous Capt. Tartarotti. With subjects tied to a chair they used iron bars and suffocating masks to extract information. Via Santa Chiara, Via Borgolocchi and Via del Piombo were among the sites, today quiet residential streets.

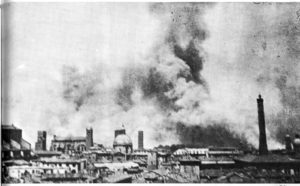

Air raid along the Bologna San Donato rail yard

City dwellers in Bologna stayed busy ducking the frequent Allied bombing raids, all of which centered on the railroad yards along the principal north-south supply route. The most devastating air raid, on September 25, 1943, went awry because of cloudy weather and over 1000 civilians died under a barrage of bombs which largely missed the railroad and hit the old city center by mistake. A month later during the Allied “Operation Pancake” the Ducati motorcycle factory, which had been retooled to produce munitions, was razed to the ground by an air raid. Because of the fighting along the Gothic Line many hill dwellers had migrated into Bologna to escape the conflict but soon found that Bologna was not immune to attack, either. Thousands of Appenine refugees poured into town, almost doubling the original population to 600,000.

Preserved Giambologna Neptune fountain in Piazza Maggiore

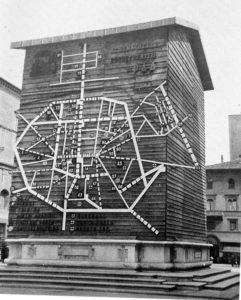

Bombproof housing to protect Neptune with city map on it

Artillery fired in Battle of Porta Lame

The “Battle of Porta Lame” was fought on November 7, 1944 when resistance fighters of the Garibaldi Brigade gathered in the part of the meat packing plant near that city gate which had been freshly bombed. German troops under the command of Gen. Gold lobbed mortars and employed a Tiger tank before moving in, only to find the structure abandoned and leaving themselves open to attack from partisans hidden around it.

Partisans stay low on Via Marconi at Aldrovandi School during Battle of Via Lame

Porta Lame surrounded by bomb destruction

SS officers confer at the Battle of Porta Lame

This resulted in a victory for the Garibaldi fighters with modest casualties on both sides: 13 each. Predictably, the Wehrmacht ordered reprisals and rounded up, over the following weeks, many partisans and anti-Fascists. The prison next to the church of San Giovanni in Monte housed many of these unfortunates; some were shipped off to lagers up north, notably Mauthausen in Austria, noted for the “Steps of Death”: 186 steps which prisoners were forced to climb repeatedly carrying sacks of granite on their shoulders. Other prisoners were instead taken to an inconspicuous part of Bologna and executed forthwith. The San Ruffillo railroad station was just such a place, with convenient bomb craters to function as mass graves. The bodies of the victims were only discovered after the war. A monument to them was erected on the site.

Togliatti as Secretary of Italian Communist Party

In 1946 Palmiro Togliatti, a Soviet-style communist with Russian citizenship, became Minister of Justice in the Italian government and penned a controversial amnesty which exonerated thousands of war criminals, many of whom were communist partisans. He had been part of the Brigata Garibaldi in Faenza and was likely responsible for many deaths himself.

Red dots mark sites of the foibe where bodies were discovered years later

In the Venezia Giulia – Trieste area bordering on Yugoslavia after the war many killings of Italians were perpetrated by Yugoslavian communists, nominally to eliminate all remaining fascists but in reality to settle private and territorial differences and to advance political power as well. Victims were dropped into foibe, deep natural pits and wells in the area, often more than 100 meters deep, in an effort to conceal the slaughter, but in later years the bodies of many were recovered. Estimates reach several thousand. Apparently the massacres were denied or at least downplayed by both the Italian and Yugoslavian governments until the 1990’s, when the subject re-emerged. Now there is a national remembrance ceremony held annually on February 10.

A “foiba”, or sinkhole

Much has been written about the Italian partisans and the subject has become somewhat of a political football. Some authors emphatically deny that many of their exploits actually occurred as stated. The partisans were a mixture of idealists, some with dreams of establishing a communist or socialist state, while others longed for democracy or even a return to monarchy. Casualties among the partisans are estimated at 45,000. There is little doubt that, right or wrong, most had the courage to die for what they believed in.

Italian POW’s liberated and returning home

Tomb of Mario Musolesi

Excellent article, well researched and written.

Excellent article, well researched and written. I enjoyed reading it.